TRIZ - The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Available Resources

Introduction

In the previous Module on Problems and Contradictions we understood how to identify an Administrative Contradiction in everyday situations. This is the first and most important step in the TRIZ Problem Solving Method.

Another important idea in TRIZ is that of Available Resources. Let us appreciate this idea with the help of a few games. But before that, a short trip to the moon NASA this time.

Available Resources: Game #1

You have to stick a lighted candle to the Wall in such a way that the melting wax does not drop on to the floor.

Available Resources: Game #2

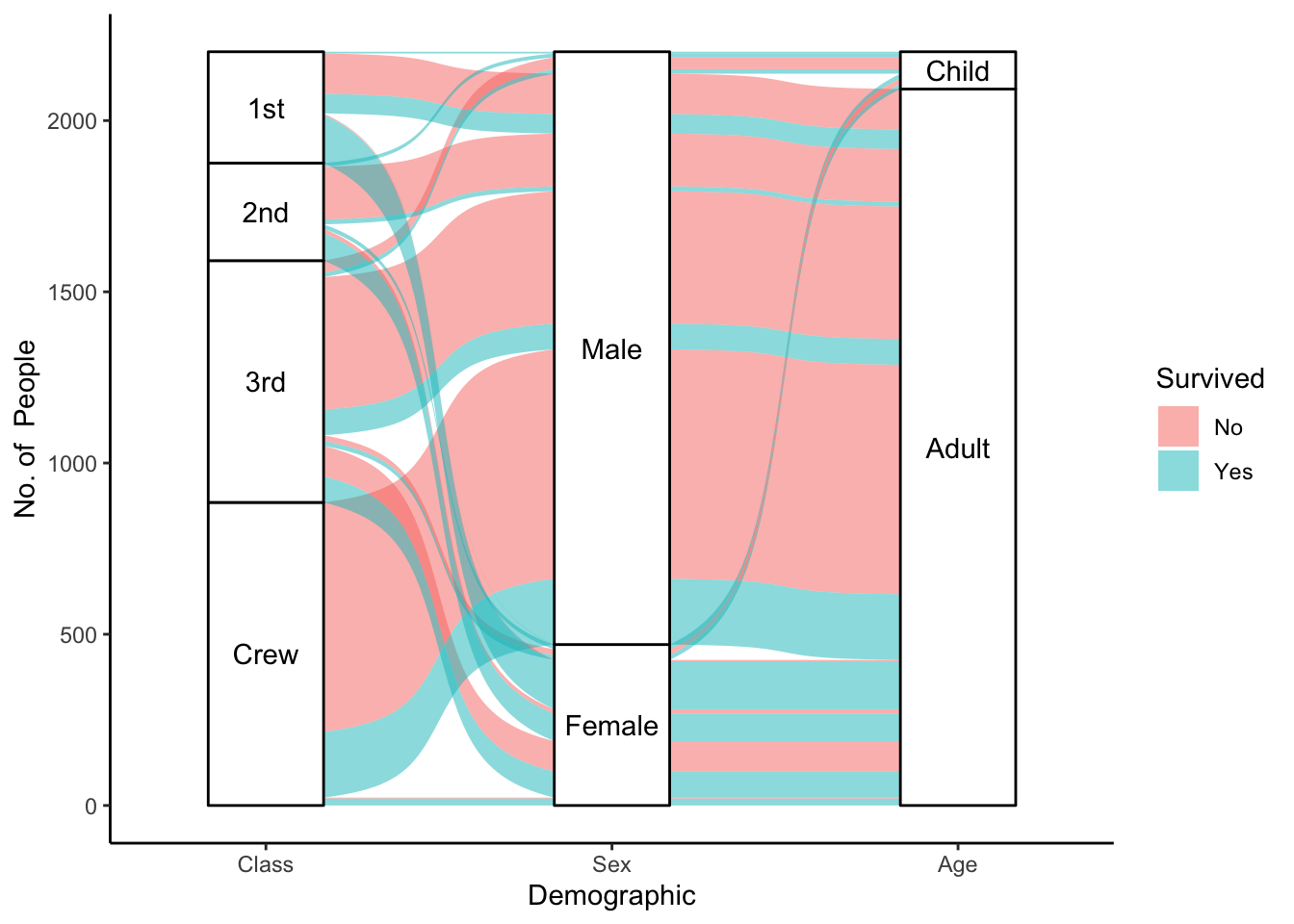

Look at the graph below: does it remind you of something you know very well?

What does this graph represent?

Let us pretend we are part of this graph and see where our Problem Formulating Skills take us!

Discussion

- Problems and Contradictions

- All Available Resources

- Assumptions and Functional Fixedness

A comparable switch of attention occurs in an old joke about a worker in a high security factory, in which the employees were carefully watched when they left at the end of their work day. On a particular day, this worker was stopped at the factory gate as he walked out with a wheelbarrow full of styrofoam packing peanuts. He explained that he had salvaged these from the trash, and was planning to use them in shipping gifts to his grandchildren. Searching through this packing material, the guards found nothing, and so they let the man go home. The following week the same thing happened, and the worker was again stopped. But he offered the very same story, and when the guards searched through the packing peanuts and found nothing, he was allowed to leave. But this continued, week after week, until the guards could no longer believe that one person would want or could make use of so much packing material. Finally, the man was held for interrogation, at which time he admitted that he had absolutely no use for packing peanuts - and that, all these weeks, he had been stealing wheelbarrows.

Hearing this joke, I am reminded of the phrase “part and parcel”, which is a rough equivalent of “figure and ground”, the Gestalt Principles. Throughout most of it, the packing peanuts occupy center stage as figure (part), while the wheelbarrows (which function merely as containers) are completely ignored as innocuous ground (parcel). At the end of the joke, there is an unexpected twist, a switch of emphasis, a recentering, when we learn that the parcel is really the part.

This should also remind us of the Guilford Alternative Uses Exercise that we did, where we forced ourselves to leave the “regular use” of an object behind and think of it as serving quite another function.

Breaking Assumptions: Making New Worlds

First, some comic relief about assumptions:

Chris Tucker seems to have discovered he had made an assumption! Luckily for him it is not too late!!

We have seen how material objects seem to have functional fixedness in our minds. There is an equivalent idea that we can relate to phenomena and processes: we can call it process fixedness. What does it entail?

Things that are stated as unchangeable:

- “We are like this only”

- “This is the way it has always be done”

- “That is not possible to change”

Sadly, there are things that are unstated and mentally unchangeable:

- have you heard of taboos?

- Secrets?

- Or things that are unmentionable because someone does not like them?

What is the METHOD by which we may discover such assumptions on phenomena/process that we place on a situation?

<< TO BE WRITTEN UP IN DETAIL.>>

References

Resources Game (PDF)

Stan Kaplan, An Introduction to TRIZ (PDF) This is a simple and short introduction to all aspects of Classical TRIZ.

Jack Hipple, “The Ideal Result: What it is and how to achieve it”, Springer, 2012.

Case Study Story

- Sahil Bloom, on X, May 6 2024:

In 2009, Stanford business professor Tina Seelig split her class into groups and issued a challenge:

Each group had $5 and 2 hours to make the highest return on the money.

At the end, they’d give a short presentation on their strategy.

What happened next was fascinating:

Most of the groups followed a simple approach:

- Use the $5 to buy a few items.

- Barter or resell those items.

- Repeat

- Sell final items for (hopefully) more than $5.

- These groups made a modest return on their initial $5.

A few groups ignored the $5. They thought up ways to make the most money in the allotted time:

- Made/sold reservations at hot restaurants.

- Refilled bike tires on campus.

- These groups made a good return on the initial USD5.

The winning group took a very different approach: They had three realizations:

- The $5 was a distraction.

- The 2 hours of time was not enough to make an attractive, outsized return with a mini-business.

- The most valuable “asset” was actually the presentation time in front of a class of Stanford students.

- Recognizing the value of the hidden asset, they offered the presentation time to Companies looking to recruit Stanford students.

- They sold the slot for

$650, a huge return on the$5of initial capital.

The winning group thought differently ( about resources ) and achieved an asymmetric outcome.